CoreRT - A .NET Runtime for AOT

07 Jun 2018 - 3018 wordsFirstly, what exactly is CoreRT? From its GitHub repo:

.. a .NET Core runtime optimized for AOT (ahead of time compilation) scenarios, with the accompanying .NET native compiler toolchain

The rest of this post will look at what that actually means.

Contents

- Existing .NET ‘AOT’ Implementations

- High-Level Overview

- The Compiler

- The Runtime

- ‘Hello World’ Program

- Limitations

- Further Reading

Existing .NET ‘AOT’ Implementations

However, before we look at what CoreRT is, it’s worth pointing out there are existing .NET ‘Ahead-of-Time’ (AOT) implementations that have been around for a while:

Mono

- Ahead of Time Compilation in Mono (August 2006)

- Mono Docs - AOT (also see this link)

- How Xamarin.Android AOT Works

- Xamarin.iOS - Architecture - AOT

.NET Native (Windows 10/UWP apps only, a.k.a ‘Project N’)

- Announcing .NET Native Preview (April 2014)

- The .NET Native Tool-Chain

- Archive of ‘.NET Native’ Blogs Posts

- Compiling Apps with .NET Native (docs)

- .NET Native – What it means for Universal Windows Platform (UWP) developers

- Introduction to .NET Native

So if there were existing implementations, why was CoreRT created? The official announcement gives us some idea:

If we want to shortcut this two-step compilation process and deliver a 100% native application on Windows, Mac, and Linux, we need an alternative to the CLR. The project that is aiming to deliver that solution with an ahead-of-time compilation process is called CoreRT.

The main difference is that CoreRT is designed to support .NET Core scenarios, i.e. .NET Standard, cross-platform, etc.

Also worth pointing out is that whilst .NET Native is a separate product, they are related and in fact “.NET Native shares many CoreRT parts”.

High-Level Overview

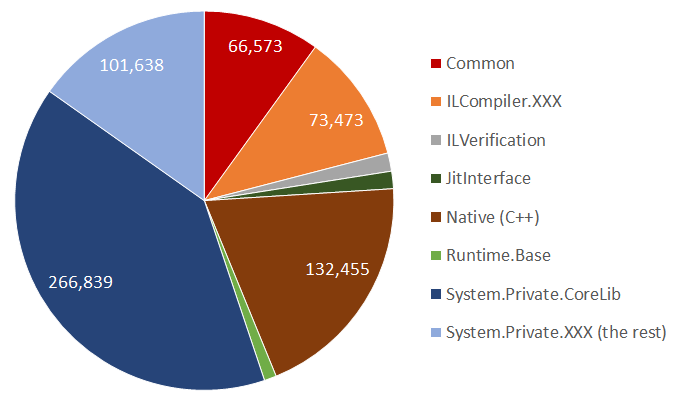

Because all the code is open source, we can very easily identify the main components and understand where the complexity is. Firstly lets look at where the most ‘lines of code’ are:

We clearly see that the majority of the code is written in C#, with only the Native component written in C++. The largest single component is System.Private.CoreLib which is all C# code, although there are other sub-components that contribute to it (‘System.Private.XXX’), such as System.Private.Interop (36,547 LOC), System.Private.TypeLoader (30,777) and System.Private.Reflection.Core (24,964). Other significant components are the ‘Intermediate Language (IL) Compiler’ and the Common code that is used re-used by everything else.

All these components are discussed in more detail below.

The Compiler

So whilst CoreRT is a run-time, it also needs a compiler to put everything together, from Intro to .NET Native and CoreRT:

.NET Native is a native toolchain that compiles CIL byte code to machine code (e.g. X64 instructions). By default, .NET Native (for .NET Core, as opposed to UWP) uses RyuJIT as an ahead-of-time (AOT) compiler, the same one that CoreCLR uses as a just-in-time (JIT) compiler. It can also be used with other compilers, such as LLILC, UTC for UWP apps and IL to CPP (an IL to textual C++ compiler we have built as a reference prototype).

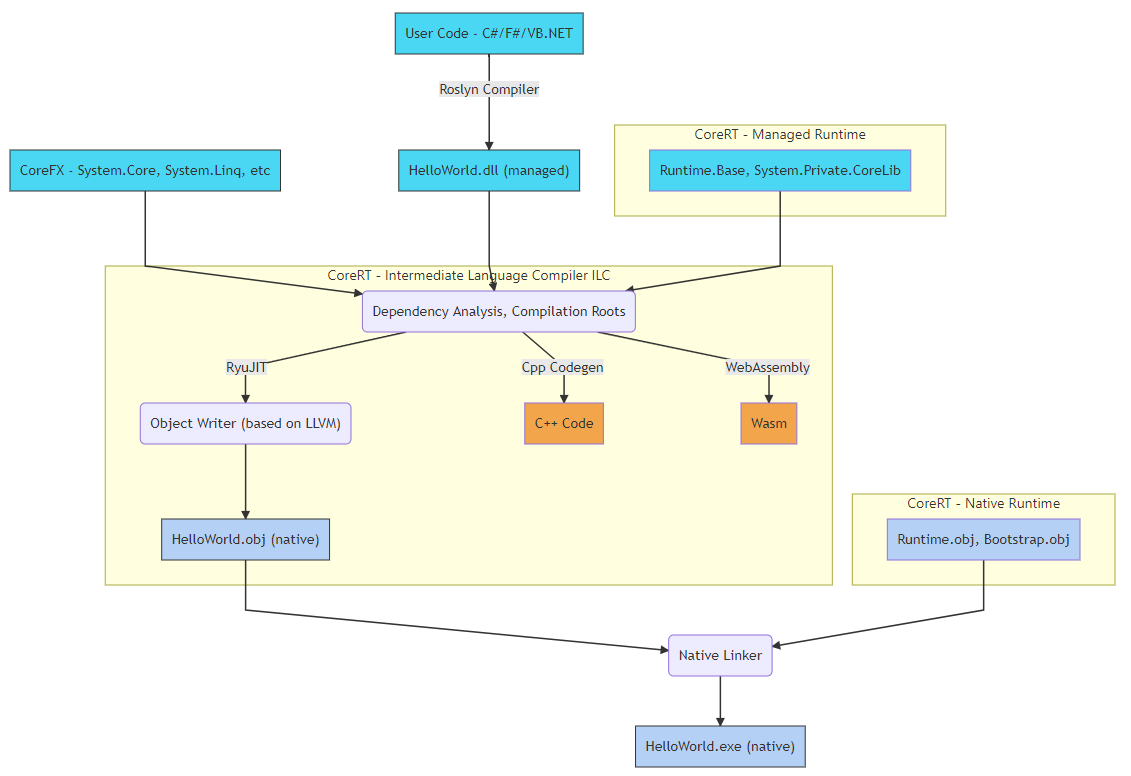

But what does this actually look like in practice, as they say ‘a picture paints a thousand words’:

(Click for larger version)

To give more detail, the main compilation phases (started from \ILCompiler\src\Program.cs) are the following:

- Calculate the reachable modules/types/classes, i.e. the ‘compilation roots’ using the ILScanner.cs

- Allow for reflection, via an optional rd.xml file and generate the necessary metadata using ILCompiler.MetadataWriter

- Compile the IL using the specific back-end (generic/shared code is in Compilation.cs)

- RyuJIT RyuJitCompilation.cs

- Web Assembly (WASM) WebAssemblyCodegenCompilation.cs

- C++ Code CppCodegenCompilation.cs

- Finally, write out the compiled methods using ObjectWriter which in turn uses LLVM under-the-hood

But it’s not just your code that ends up in the final .exe, along the way the CoreRT compiler also generates several ‘helper methods’ to cover the following scenarios:

- IL Code (via the ‘EmitIL()’ method)

- Assembly Code (via the ‘EmitCode()’ method) (different implementaions for each CPU architecure)

- Unboxing (x64)

- Jump Stubs (ARM64)

- ‘Ready to Run’ Generic helper (x86)

Fortunately the compiler doesn’t blindly include all the code it finds, it is intelligent enough to only include code that’s actually used:

We don’t use ILLinker, but everything gets naturally treeshaken by the compiler itself (we start with compiling

Main/NativeCallableexports and continue compiling other methods and generating necessary data structures as we go). If there’s a type or method that is not used, the compiler doesn’t even look at it.

The Runtime

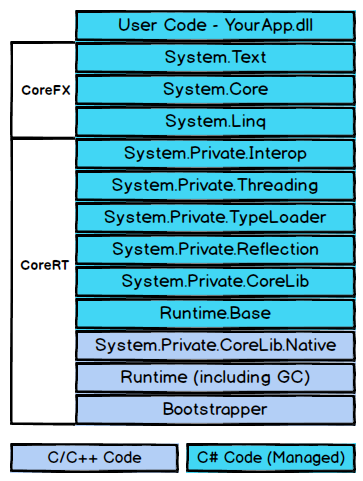

All the user/helper code then sits on-top of the CoreRT runtime, from Intro to .NET Native and CoreRT:

CoreRT is the .NET Core runtime that is optimized for AOT scenarios, which .NET Native targets. This is a refactored and layered runtime. The base is a small native execution engine that provides services such as garbage collection(GC). This is the same GC used in CoreCLR. Many other parts of the traditional .NET runtime, such as the type system, are implemented in C#. We’ve always wanted to implement runtime functionality in C#. We now have the infrastructure to do that. In addition, library implementations that were built deep into CoreCLR, have also been cleanly refactored and implemented as C# libraries.

This last point is interesting, why is it advantageous to implement ‘runtime functionality in C#’? Well it turns out that it’s hard to do in an un-managed language because there’s some very subtle and hard-to-track-down ways that you can get it wrong:

Reliability and performance. The C/C++ code has to manually managed. It means that one has to be very careful to report all GC references to the GC. The manually managed code is both very hard to get right and it has performance overhead.

— Jan Kotas (@JanKotas7) April 24, 2018

These are known as ‘GC Holes’ and the BOTR provides more detail on them. The author of that tweet is significant, Jan Kotas has worked on the .NET runtime for a long time, if he thinks something is hard, it really is!!

Runtime Components

As previously mentioned it’s a layered runtime, i.e made up of several, distinct components, as explained in this comment:

At the core of CoreRT, there’s a runtime that provides basic services for the code to run (think: garbage collection, exception handling, stack walking). This runtime is pretty small and mostly depends on C/C++ runtime (even the C++ runtime dependency is not a hard requirement as Jan pointed out - #3564). This code mostly lives in src/Native/Runtime, src/Native/gc, and src/Runtime.Base. It’s structured so that the places that do require interacting with the underlying platform (allocating native memory, threading, etc.) go through a platform abstraction layer (PAL). We have a PAL for Windows, Linux, and macOS, but others can be added.

And you can see the PAL Components in the following locations:

C# Code shared with CoreCLR

One interesting aspect of the CoreRT runtime is that wherever possible it shares code with the CoreCLR runtime, this is part of a larger effort to ensure that wherever possible code is shared across multiple repositories:

This directory contains the shared sources for System.Private.CoreLib. These are shared between dotnet/corert, dotnet/coreclr and dotnet/corefx. The sources are synchronized with a mirroring tool that watches for new commits on either side and creates new pull requests (as @dotnet-bot) in the other repository.

Recently there has been a significant amount of work done to moved more and more code over into the ‘shared partition’ to ensure work isn’t duplicated and any fixes are shared across both locations. You can see how this works by looking at the links below:

- CoreRT

- CoreCLR

What this means is that about 2/3 of the C# code in System.Private.CoreLib is shared with CoreCLR and only 1/3 is unique to CoreRT:

| Group | C# LOC (Files) |

|---|---|

| shared | 170,106 (759) |

| src | 96,733 (351) |

| Total | 266,839 (1,110) |

Native Code

Finally, whilst it is advantageous to write as much code as possible in C#, there are certain components that have to be written in C++, these include the GC (the majority of which is one file, gc.cpp which is almost 37,000 LOC!!), the JIT Interface, ObjWriter (based on LLVM) and most significantly the Core Runtime that contains code for activities like:

- Threading

- Stack Frame handling

- Debugging/Profiling

- Interfacing to the OS

- CPU specific helpers for:

- Exception handling

- GC Write Barriers

- Stubs/Thunks

- Optimised object allocation

‘Hello World’ Program

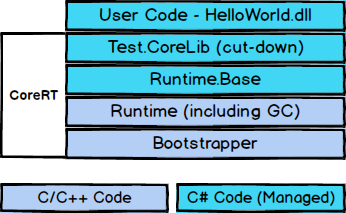

One of the first things people asked about CoreRT is “what is the size of a ‘Hello World’ app” and the answer is ~3.93 MB (if you compile in Release mode), but there is work being done to reduce this. At a ‘high-level’, the .exe that is produced looks like this:

Note the different colours correspond to the original format of a component, obviously the output is a single, native, executable file.

This file comes with a full .NET specific ‘base runtime’ or ‘class libraries’ (‘System.Private.XXX’) so you get a lot of functionality, it is not the absolute bare-minimum app. Fortunately there is a way to see what a ‘bare-minimum’ runtime would look like by compiling against the Test.CoreLib project included in the CoreRT source. By using this you end up with an .exe that looks like this:

But it’s so minimal that OOTB you can’t even write ‘Hello World’ to the console as there is no System.Console type! After a bit of hacking I was able to build a version that did have a working Console output (if you’re interested, this diff is available here). To make it work I had to include the following components:

- System.Console

- System.Text.UnicodeEncoding

- String handling

- P/Invoke and Marshalling support (to call an OS function)

So Test.CoreLib really is a minimal runtime!! But the difference in size is dramatic, it shrinks down to 0.49 MB compared to 3.93 MB for the fully-featured runtime!

| Type | Standard (bytes) | Test.CoreLib (bytes) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| .data | 163,840 | 36,864 | -126,976 |

| .managed | 1,540,096 | 65,536 | -1,474,560 |

| .pdata | 147,456 | 20,480 | -126,976 |

| .rdata | 1,712,128 | 81,920 | -1,630,208 |

| .reloc | 98,304 | 4,096 | -94,208 |

| .text | 360,448 | 299,008 | -61,440 |

| rdata | 98,304 | 4,096 | -94,208 |

| Total (bytes) | 4,120,576 | 512,000 | -3,608,576 |

| Total (MB) | 3.93 | 0.49 | -3.44 |

These data sizes were obtained by using the Microsoft DUMPBIN tool and the /DISASM cmd line switch (zip file of the full ouput), which produces the following summary (note: size values are in HEX):

Summary

28000 .data

178000 .managed

24000 .pdata

1A2000 .rdata

18000 .reloc

58000 .text

18000 rdata

Also contained in the output is the assembly code for a simple Hello World method:

HelloWorld_HelloWorld_Program__Main:

0000000140004C50: 48 8D 0D 19 94 37 lea rcx,[__Str_Hello_World__E63BA1FD6D43904697343A373ECFB93457121E4B2C51AF97278C431E8EC85545]

00

0000000140004C57: 48 8D 05 DA C5 00 lea rax,[System_Console_System_Console__WriteLine_12]

00

0000000140004C5E: 48 FF E0 jmp rax

0000000140004C61: 90 nop

0000000140004C62: 90 nop

0000000140004C63: 90 nop

and if we dig further we can see the code for System.Console.WriteLine(..):

System_Console_System_Console__WriteLine_12:

0000000140011238: 56 push rsi

0000000140011239: 48 83 EC 20 sub rsp,20h

000000014001123D: 48 8B F1 mov rsi,rcx

0000000140011240: E8 33 AD FF FF call System_Console_System_Console__get_Out

0000000140011245: 48 8B C8 mov rcx,rax

0000000140011248: 48 8B D6 mov rdx,rsi

000000014001124B: 48 8B 00 mov rax,qword ptr [rax]

000000014001124E: 48 8B 40 68 mov rax,qword ptr [rax+68h]

0000000140011252: 48 83 C4 20 add rsp,20h

0000000140011256: 5E pop rsi

0000000140011257: 48 FF E0 jmp rax

000000014001125A: 90 nop

000000014001125B: 90 nop

Limitations

Missing Functionality

There have been some people who’ve successfully run complex apps using CoreRT, but, as it stands CoreRT is still an alpha product. At least according to the NuGet package ‘1.0.0-alpha-26529-02’ that the official samples instruct you to use and I’ve not seen any information about when a full 1.0 Release will be available.

So there is some functionality that is not yet implemented, e.g. F# Support, GC.GetMemoryInfo or canGetCookieForPInvokeCalliSig (a calli to a p/invoke). For more information on this I recommend this entertaining presentation on Building Native Executables from .NET with CoreRT by Mark Rendle. In the 2nd half he chronicles all the issues that he ran into when he was trying to run an ASP.NET app under CoreRT (some of which may well be fixed now).

Reflection

But more fundamentally, because of the nature of AOT compilation, there are 2 main stumbling blocks that you may also run into Reflection and Runtime Code-Generation.

Firstly, if you want to use reflection in your code you need to tell the CoreRT compiler about the types you expect to reflect over, because by-default it only includes the types it knows about. You can do with by using a file called rd.xml as shown here. Unfortunately this will always require manual intervention for the reasons explained in this issue. More information is available in this comment ‘…some details about CoreRT’s restriction on MakeGenericType and MakeGenericMethod’.

To make reflection work the compiler adds the required metadata to the final .exe using this process:

This would reuse the same scheme we already have for the RyuJIT codegen path:

- The compiler generates a blob of bytes that describes the metadata (namespaces, types, their members, their custom attributes, method parameters, etc.). The data is generated as a byte array in the ComputeMetadata method.

- The metadata gets embedded as a data blob into the executable image. This is achieved by adding the blob to a “ready to run header”. Ready to run header is a well known data structure that can be located by the code in the framework at runtime.

- The ready to run header along with the blobs it refers to is emitted into the final executable.

- At runtime, pointer to the byte array is located using the RhFindBlob API, and a parser is constructed over the array, to be used by the reflection stack.

Runtime Code-Generation

In .NET you often use reflection once (because it can be slow) followed by ‘dynamic’ or ‘runtime’ code-generation with Reflection.Emit(..). This technique is widely using in .NET libraries for Serialisation/Deserialisation, Dependency Injection, Object Mapping and ORM.

The issue is that ‘runtime’ code generation is problematic in an ‘AOT’ scenario:

ASP.NET dependency injection introduced dependency on Reflection.Emit in aspnet/DependencyInjection#630 unfortunately. It makes it incompatible with CoreRT.

We can make it functional in CoreRT AOT environment by introducing IL interpretter (#5011), but it would still perform poorly. The dependency injection framework is using Reflection.Emit on performance critical paths.

It would be really up to ASP.NET to provide AOT-friendly flavor that generates all code at build time instead of runtime to make this work well. It would likely help the startup without CoreRT as well.

I’m sure this will be solved one way or the other (see #5011), but at the moment it’s still ‘work-in-progress’.

Discuss this post on HackerNews and /r/dotnet

Further Reading

If you’ve got this far, here’s some other links that you might be interested in:

- What’s the difference between .NET CoreCLR, CoreRT, Roslyn and LLILC

- What I’ve learned about .NET Native

- Channel 9 - CoreRT & .NET Native

- Channel 9 - Going Deep - Inside .NET Native

- Building ILCompiler in Visual Studio 2017

- Type System Overview (botr)

- Interfaces API surface on Type System

- How Xamarin.Android AOT Works

- An introduction to IL2CPP internals

- .NET Native Performance and Internals

- Dynamic Tracing of .NET Core Methods

- Generic sharing for valuetypes (Mono)

- .NET Internals and Native Compiling