DotNetAnywhere: An Alternative .NET Runtime

19 Oct 2017 - 3158 wordsRecently I was listening to the excellent DotNetRocks podcast and they had Steven Sanderson (of Knockout.js fame) talking about ‘WebAssembly and Blazor’.

In case you haven’t heard about it, Blazor is an attempt to bring .NET to the browser, using the magic of WebAssembly. If you want more info, Scott Hanselmen has done a nice write-up of the various .NET/WebAssembly projects.

However, as much as the mention of WebAssembly was pretty cool, what interested me even more how Blazor was using DotNetAnywhere as the underlying .NET runtime. This post will look at what DotNetAnywhere is, what you can do with it and how it compares to the full .NET framework.

DotNetAnywhere

Firstly it’s worth pointing out that DotNetAnywhere (DNA) is designed to be a fully compliant .NET runtime, which means that it can run .NET dlls/exes that have been compiled to run against the full framework. On top of that (at least in theory) it supports all the following .NET runtime features, which is a pretty impressive list!

- Generics

- Garbage collection and finalization

- Weak references

- Full exception handling - try/catch/finally

- PInvoke

- Interfaces

- Delegates

- Events

- Nullable types

- Single-dimensional arrays

- Multi-threading

In addition there is some partial support for Reflection

- Very limited read-only reflection

- typeof(), .GetType(), Type.Name, Type.Namespace, Type.IsEnum(), <object>.ToString() only

Finally, there are a few features that are currently unsupported:

- Attributes

- Most reflection

- Multi-dimensional arrays

- Unsafe code

There are various bugs or missing functionality that might prevent your code running under DotNetAnywhere, however several of these have been fixed since Blazor came along, so it’s worth checking against the Blazor version of DotNetAnywhere.

At this point in time the original DotNetAnywhere repo is no longer active (the last sustained activity was in Jan 2012), so it seems that any future development or bugs fixes will likely happen in the Blazor repo. If you have ever fixed something in DotNetAnywhere, consider sending a P.R there, to help the effort.

Update: In addition there are other forks with various bug fixes and enhancements:

Source Code Layout

What I find most impressive about the DotNetAnywhere runtime is that it was developed by one person and is less that 40,000 lines of code!! For a comparison the .NET framework Garbage Collector is almost 37,000 lines on it’s own (more info available in my previous post A Hitchhikers Guide to the CoreCLR Source Code).

This makes DotNetAnywhere an ideal learning resource!

Firstly, lets take a look at the Top-10 largest source files, to see where the complexity is:

Native Code - 17,710 lines in total

| LOC | File |

|---|---|

| 3,164 | JIT_Execute.c |

| 1,778 | JIT.c |

| 1,109 | PInvoke_CaseCode.h |

| 630 | Heap.c |

| 618 | MetaData.c |

| 563 | MetaDataTables.h |

| 517 | Type.c |

| 491 | MetaData_Fill.c |

| 467 | MetaData_Search.c |

| 452 | JIT_OpCodes.h |

Managed Code - 28,783 lines in total

Main areas of functionality

Next, lets look at the key components in DotNetAnywhere as this gives us a really good idea about what you need to implement a .NET compatible runtime. Along the way, we will also see how they differ from the implementation found in Microsoft’s .NET Framework.

Reading .NET dlls

The first thing DotNetAnywhere has to do is read/understand/parse the .NET Metadata and Code that’s contained in a .dll/.exe. This all takes place in MetaData.c, primarily within the LoadSingleTable(..) function. By adding some debugging code, I was able to get a summary of all the different types of Metadata that are read in from a typical .NET dll, it’s quite an interesting list:

MetaData contains 1 Assemblies (MD_TABLE_ASSEMBLY)

MetaData contains 1 Assembly References (MD_TABLE_ASSEMBLYREF)

MetaData contains 0 Module References (MD_TABLE_MODULEREF)

MetaData contains 40 Type References (MD_TABLE_TYPEREF)

MetaData contains 13 Type Definitions (MD_TABLE_TYPEDEF)

MetaData contains 14 Type Specifications (MD_TABLE_TYPESPEC)

MetaData contains 5 Nested Classes (MD_TABLE_NESTEDCLASS)

MetaData contains 11 Field Definitions (MD_TABLE_FIELDDEF)

MetaData contains 0 Field RVA's (MD_TABLE_FIELDRVA)

MetaData contains 2 Propeties (MD_TABLE_PROPERTY)

MetaData contains 59 Member References (MD_TABLE_MEMBERREF)

MetaData contains 2 Constants (MD_TABLE_CONSTANT)

MetaData contains 35 Method Definitions (MD_TABLE_METHODDEF)

MetaData contains 5 Method Specifications (MD_TABLE_METHODSPEC)

MetaData contains 4 Method Semantics (MD_TABLE_PROPERTY)

MetaData contains 0 Method Implementations (MD_TABLE_METHODIMPL)

MetaData contains 22 Parameters (MD_TABLE_PARAM)

MetaData contains 2 Interface Implementations (MD_TABLE_INTERFACEIMPL)

MetaData contains 0 Implementation Maps? (MD_TABLE_IMPLMAP)

MetaData contains 2 Generic Parameters (MD_TABLE_GENERICPARAM)

MetaData contains 1 Generic Parameter Constraints (MD_TABLE_GENERICPARAMCONSTRAINT)

MetaData contains 22 Custom Attributes (MD_TABLE_CUSTOMATTRIBUTE)

MetaData contains 0 Security Info Items? (MD_TABLE_DECLSECURITY)

For more information on the Metadata see Introduction to CLR metadata, Anatomy of a .NET Assembly – PE Headers and the ECMA specification itself.

Executing .NET IL

Another large piece of functionality within DotNetAnywhere is the ‘Just-in-Time’ Compiler (JIT), i.e. the code that is responsible for executing the IL, this takes place initially in JIT_Execute.c and then JIT.c. The main ‘execution loop’ is in the JITit(..) function which contains an impressive 1,374 lines of code and over 200 case statements within a single switch!!

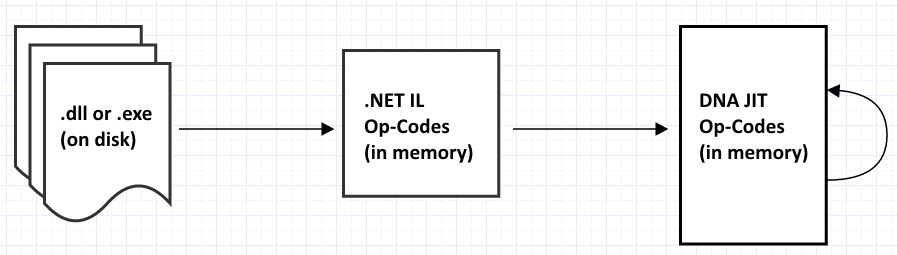

Taking a higher level view, the overall process that it goes through looks like this:

Where the .NET IL Op-Codes (CIL_XXX) are defined in CIL_OpCodes.h and the DotNetAnywhere JIT Op-Codes (JIT_XXX) are defined in JIT_OpCodes.h

Interesting enough, the JIT is the only place in DotNetAnywhere that uses assembly code and even then it’s only for win32. It is used to allow a ‘jump’ or a goto to labels in the C source code, so as IL instructions are executed it never actually leaves the JITit(..) function, control is just moved around without having to make a full method call.

#ifdef __GNUC__

#define GET_LABEL(var, label) var = &&label

#define GO_NEXT() goto **(void**)(pCurOp++)

#else

#ifdef WIN32

#define GET_LABEL(var, label) \

{ __asm mov edi, label \

__asm mov var, edi }

#define GO_NEXT() \

{ __asm mov edi, pCurOp \

__asm add edi, 4 \

__asm mov pCurOp, edi \

__asm jmp DWORD PTR [edi - 4] }

#endif

Differences with the .NET Framework

In the full .NET framework all IL code is turned into machine code by the Just-in-Time Compiler (JIT) before being executed by the CPU.

However as we’ve already seen, DotNetAnywhere ‘interprets’ the IL, instruction-by-instruction and even through it’s done in a file called JIT.c no machine code is emitted, so the naming seems strange!?

Maybe it’s just a difference of perspective, but it’s not clear to me at what point you move from ‘interpreting’ code to ‘JITting’ it, even after reading the following links I’m not sure!! (can someone enlighten me?)

- What are the differences between a Just-in-Time-Compiler and an Interpreter?

- Understanding the differences: traditional interpreter, JIT compiler, JIT interpreter and AOT compiler

- JIT vs Interpreters

- Why do we call it “JIT compiler” and not “JIT interpreter” to refer to the thing that converts the Java bytecode to the machine code?

- Understanding JIT Compilation and Optimizations

Garbage Collector

All the code for the DotNetAnywhere Garbage Collector (GC) is contained in Heap.c and is a very readable 600 lines of code. To give you an overview of what it does, here is the list of functions that it exposes:

void Heap_Init();

void Heap_SetRoots(tHeapRoots *pHeapRoots, void *pRoots, U32 sizeInBytes);

void Heap_UnmarkFinalizer(HEAP_PTR heapPtr);

void Heap_GarbageCollect();

U32 Heap_NumCollections();

U32 Heap_GetTotalMemory();

HEAP_PTR Heap_Alloc(tMD_TypeDef *pTypeDef, U32 size);

HEAP_PTR Heap_AllocType(tMD_TypeDef *pTypeDef);

void Heap_MakeUndeletable(HEAP_PTR heapEntry);

void Heap_MakeDeletable(HEAP_PTR heapEntry);

tMD_TypeDef* Heap_GetType(HEAP_PTR heapEntry);

HEAP_PTR Heap_Box(tMD_TypeDef *pType, PTR pMem);

HEAP_PTR Heap_Clone(HEAP_PTR obj);

U32 Heap_SyncTryEnter(HEAP_PTR obj);

U32 Heap_SyncExit(HEAP_PTR obj);

HEAP_PTR Heap_SetWeakRefTarget(HEAP_PTR target, HEAP_PTR weakRef);

HEAP_PTR* Heap_GetWeakRefAddress(HEAP_PTR target);

void Heap_RemovedWeakRefTarget(HEAP_PTR target);

Differences with the .NET Framework

However, like the JIT/Interpreter, the GC has some fundamental differences when compared to the .NET Framework

Conservative Garbage Collection

Firstly DotNetAnywhere implements what is knows as a Conservative GC. In simple terms this means that is does not know (for sure) which areas of memory are actually references/pointers to objects and which are just a random number (that looks like a memory address). In the Microsoft .NET Framework the JIT calculates this information and stores it in the GCInfo structure so the GC can make use of it. But DotNetAnywhere doesn’t do this.

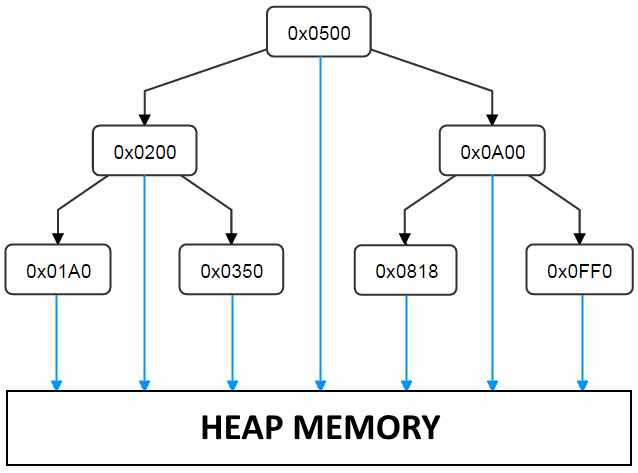

Instead, during the Mark phase the GC gets all the available ‘roots’, but it will consider all memory addresses within an object as ‘potential’ references (hence it is ‘conservative’). It then has to lookup each possible reference, to see if it really points to an ‘object reference’. It does this by keeping track of all memory/heap references in a balanced binary search tree (ordered by memory address), which looks something like this:

However, this means that all objects references have to be stored in the binary tree when they are allocated, which adds some overhead to allocation. In addition extra memory is needed, 20 bytes per heap entry. We can see this by looking at the tHeapEntry data structure (all pointers are 4 bytes, U8 = 1 byte and padding is ignored), tHeapEntry *pLink[2] is the extra data that is needed just to enable the binary tree lookup.

struct tHeapEntry_ {

// Left/right links in the heap binary tree

tHeapEntry *pLink[2];

// The 'level' of this node. Leaf nodes have lowest level

U8 level;

// Used to mark that this node is still in use.

// If this is set to 0xff, then this heap entry is undeletable.

U8 marked;

// Set to 1 if the Finalizer needs to be run.

// Set to 2 if this has been added to the Finalizer queue

// Set to 0 when the Finalizer has been run (or there is no Finalizer in the first place)

// Only set on types that have a Finalizer

U8 needToFinalize;

// unused

U8 padding;

// The type in this heap entry

tMD_TypeDef *pTypeDef;

// Used for locking sync, and tracking WeakReference that point to this object

tSync *pSync;

// The user memory

U8 memory[0];

};

But why does DotNetAnywhere work like this? Fortunately Chris Bacon the author of DotNetAnywhere explains

Mind you, the whole heap code really needs a rewrite to reduce per-object memory overhead, and to remove the need for the binary tree of allocations. Not really thinking of a generational GC, that would probably add to much code. This was something I vaguely intended to do, but never got around to. The current heap code was just the simplest thing to get GC working quickly. The very initial implementation did no GC at all. It was beautifully fast, but ran out of memory rather too quickly.

For more info on ‘Conservative’ and ‘Precise’ GCs see:

- Precise vs. conservative and internal pointers

- How does the .NET CLR distinguish between Managed from Unmanaged Pointers?

GC only does ‘Mark-Sweep’, it doesn’t Compact

Another area in which the GC behaviour differs is that it doesn’t do any Compaction of memory after it’s cleaned up, as Steve Sanderson found out when working on Blazor

.. During server-side execution we don’t actually need to pin anything, because there’s no interop outside .NET. During client-side execution, everything is (in effect) pinned regardless, because DNA’s GC only does mark-sweep - it doesn’t have any compaction phase.

In addition, when an object is allocated DotNetAnywhere just makes a call to malloc(), see the code that does this is in the Heap_Alloc(..) function. So there is no concept of ‘Generations’ or ‘Segments’ that you have in the .NET Framework GC, i.e. no ‘Gen 0’, ‘Gen 1’, or ‘Large Object Heap’.

Threading Model

Finally, lets take a look at the threading model, which is fundamentally different from the one found in the .NET Framework.

Differences with the .NET Framework

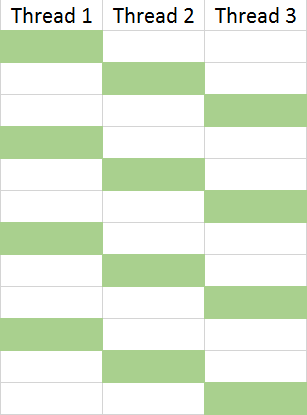

Whilst DotNetAnywhere will happily create new threads and execute them for you, it’s only providing the illusion of true multi-threading. In reality it only runs on one thread, but context switches between the different threads that your program creates:

You can see this in action in the code below, (from the Thread_Execute() function), note the call to JIT_Execute(..) with numInst set to 100:

for (;;) {

U32 minSleepTime = 0xffffffff;

I32 threadExitValue;

status = JIT_Execute(pThread, 100);

switch (status) {

....

}

}

An interesting side-effect is that the threading code in the DotNetAnywhere corlib implementation is really simple. For instance the internal implementation of the Interlocked.CompareExchange() function looks like the following, note the lack of synchronisation that you would normally expect:

tAsyncCall* System_Threading_Interlocked_CompareExchange_Int32(

PTR pThis_, PTR pParams, PTR pReturnValue) {

U32 *pLoc = INTERNALCALL_PARAM(0, U32*);

U32 value = INTERNALCALL_PARAM(4, U32);

U32 comparand = INTERNALCALL_PARAM(8, U32);

*(U32*)pReturnValue = *pLoc;

if (*pLoc == comparand) {

*pLoc = value;

}

return NULL;

}

Benchmarks

As a simple test, I ran some benchmarks from The Computer Language Benchmarks Game - binary-trees, using the simplest C# version

Note: DotNetAnywhere was designed to run on low-memory devices, so it was not meant to have the same performance as the full .NET Framework. Please bear that in mind when looking at the results!!

.NET Framework, 4.6.1 - 0.36 seconds

Invoked=TestApp.exe 15

stretch tree of depth 16 check: 131071

32768 trees of depth 4 check: 1015808

8192 trees of depth 6 check: 1040384

2048 trees of depth 8 check: 1046528

512 trees of depth 10 check: 1048064

128 trees of depth 12 check: 1048448

32 trees of depth 14 check: 1048544

long lived tree of depth 15 check: 65535

Exit code : 0

Elapsed time : 0.36

Kernel time : 0.06 (17.2%)

User time : 0.16 (43.1%)

page fault # : 6604

Working set : 25720 KB

Paged pool : 187 KB

Non-paged pool : 24 KB

Page file size : 31160 KB

DotNetAnywhere - 54.39 seconds

Invoked=dna TestApp.exe 15

stretch tree of depth 16 check: 131071

32768 trees of depth 4 check: 1015808

8192 trees of depth 6 check: 1040384

2048 trees of depth 8 check: 1046528

512 trees of depth 10 check: 1048064

128 trees of depth 12 check: 1048448

32 trees of depth 14 check: 1048544

long lived tree of depth 15 check: 65535

Total execution time = 54288.33 ms

Total GC time = 36857.03 ms

Exit code : 0

Elapsed time : 54.39

Kernel time : 0.02 (0.0%)

User time : 54.15 (99.6%)

page fault # : 5699

Working set : 15548 KB

Paged pool : 105 KB

Non-paged pool : 8 KB

Page file size : 13144 KB

So clearly DotNetAnywhere doesn’t work as fast in this benchmark (0.36 seconds v 54 seconds). However if we look at other benchmarks from the same site, it performs a lot better. It seems that DotNetAnywhere has a significant overhead when allocating objects (a class), which is less obvious when using structs.

Benchmark 1 (using classes) |

Benchmark 2 (using structs) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Elapsed Time (secs) | 3.1 | 2.0 |

| GC Collections | 96 | 67 |

| Total GC time (msecs) | 983.59 | 439.73 |

Finally, I really want to thank Chris Bacon, DotNetAnywhere is a great code base and gives a fantastic insight into what needs to happen for a .NET runtime to work.

Discuss this post on Hacker News and /r/programming