Why Exceptions should be Exceptional

20 Dec 2016 - 1999 words

According to the NASA ‘Near Earth Object Program’ asteroid ‘101955 Bennu (1999 RQ36)’ has a Cumulative Impact Probability of 3.7e-04, i.e. there is a 1 in 2,700 (0.0370%) chance of Earth impact, but more reassuringly there is a 99.9630% chance the asteroid will miss the Earth completely!

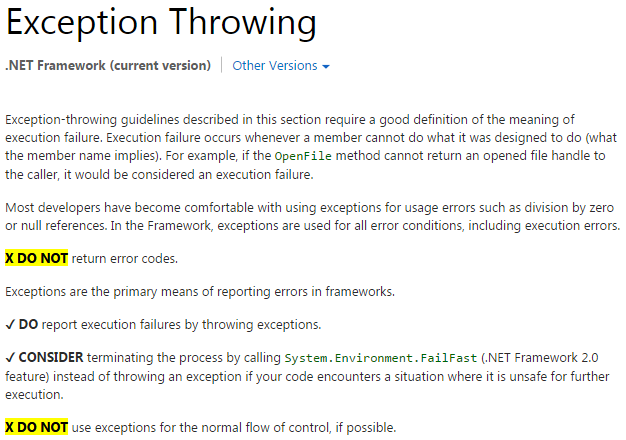

But how does this relate to exceptions in the .NET runtime, well let’s take a look at the official .NET Framework Design Guidelines for Throwing Exceptions (which are based on the excellent book Framework Design Guidelines: Conventions, Idioms, and Patterns for Reusable .NET Libraries)

So exceptions should be exceptional, unusual or rare, much like a asteroid strike!!

.NET Framework TryXXX() Pattern

In .NET, the recommended was to avoid exceptions in normal code flow is to use the TryXXX() pattern. As pointed out in the guideline section on Exceptions and Performance, rather than writing code like this, which has to catch the exception when the input string isn’t a valid integer:

try

{

int result = int.Parse("IANAN");

Console.WriteLine(result);

}

catch (FormatException fEx)

{

Console.WriteLine(fEx);

}

You should instead use the TryXXX API, in the following pattern:

int result;

if (int.TryParse("IANAN", out result))

{

// SUCCESS!!

Console.WriteLine(result);

}

else

{

// FAIL!!

}

Fortunately large parts of the .NET runtime use this pattern for non-exceptional events, such as parsing a string, creating a URL or adding an item to a Concurrent Dictionary.

The performance costs of exceptions

So onto the performance costs, I was inspired to write this post after reading this tweet from Clemens Vasters:

I also copied/borrowed a large amount of ideas from the excellent post ‘The Exceptional Performance of Lil’ Exception’ by Java performance guru Aleksey Shipilëv (this post is in essence the .NET version of his post, which focuses exclusively on exceptions in the JVM)

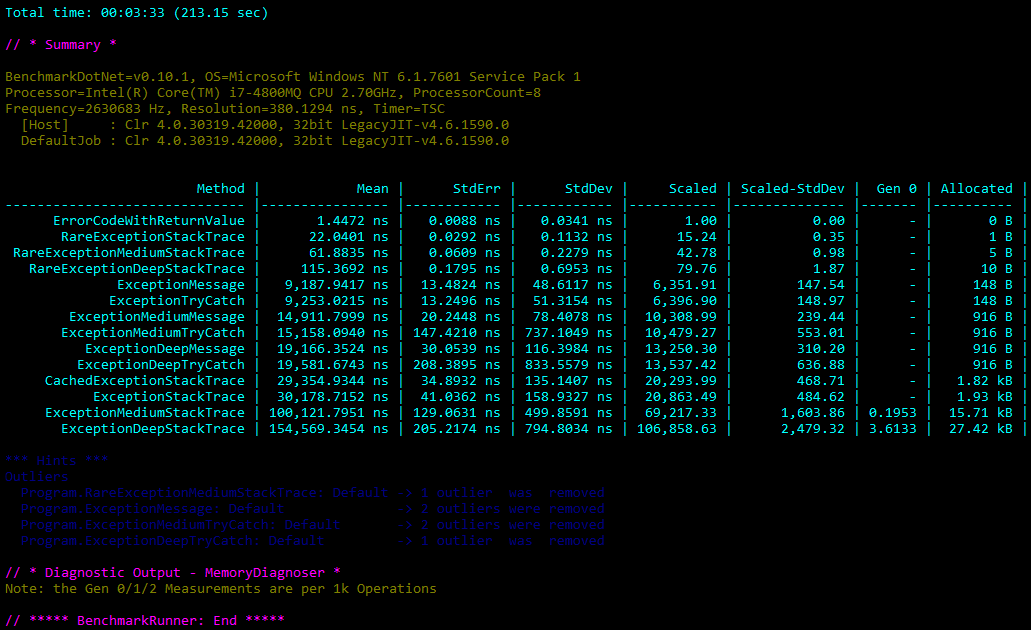

So lets start with the full results (click for full-size image):

(Full Benchmark Code and Results)

Rare exceptions v Error Code Handling

Up front I want to be clear that nothing in this post is meant to contradict the best-practices outlined in the .NET Framework Guidelines (above), in fact I hope that it actually backs them up!

| Method | Mean | StdErr | StdDev | Scaled |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ErrorCodeWithReturnValue | 1.4472 ns | 0.0088 ns | 0.0341 ns | 1.00 |

| RareExceptionStackTrace | 22.0401 ns | 0.0292 ns | 0.1132 ns | 15.24 |

| RareExceptionMediumStackTrace | 61.8835 ns | 0.0609 ns | 0.2279 ns | 42.78 |

| RareExceptionDeepStackTrace | 115.3692 ns | 0.1795 ns | 0.6953 ns | 79.76 |

Here we can see that as long as you follow the guidance and ‘DO NOT use exceptions for the normal flow of control’ then they are actually not that costly. I mean yes, they’re 15 times slower than using error codes, but we’re only talking about 22 nanoseconds, i.e. 22 billionths of a second, you have to be throwing exceptions frequently for it to be noticeable. For reference, here’s what the code for the first 2 results looks like:

public struct ResultAndErrorCode<T>

{

public T Result;

public int ErrorCode;

}

[Benchmark(Baseline = true)]

public ResultAndErrorCode<string> ErrorCodeWithReturnValue()

{

var result = new ResultAndErrorCode<string>();

result.Result = null;

result.ErrorCode = 5;

return result;

}

[Benchmark]

public string RareExceptionStackTrace()

{

try

{

RareLevel20(); // start all the way down

return null; //Prevent Error CS0161: not all code paths return a value

}

catch (InvalidOperationException ioex)

{

// Force collection of a full StackTrace

return ioex.StackTrace;

}

}

Where the ‘RareLevelXX() functions look like this (i.e. will only trigger an exception once for every 2,700 times it’s called):

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)]

private static void RareLevel1() { RareLevel2(); }

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)]

private static void RareLevel2() { RareLevel3(); }

... // several layers left out!!

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)]

private static void RareLevel19() { RareLevel20(); }

[MethodImpl(MethodImplOptions.NoInlining)]

private static void RareLevel20()

{

counter++;

// will *rarely* happen (1 in 2700)

if (counter % chanceOfAsteroidHit == 1)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Deep Stack Trace - Rarely triggered");

}

Therefore RareExceptionMediumStackTrace() just calls RareLevel10() to get a medium stack trace and RareExceptionDeepStackTrace() calls RareLevel1() which triggers the full/deep one (the full benchmark code is available).

Stack traces

Now that we’ve seen the cost of calling exceptions rarely, we’re going to look at the effect the stack trace depth has on performance. Here are the full, raw results:

| Method | Mean | StdErr | StdDev | Gen 0 | Allocated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exception-Message | 9,187.9417 ns | 13.4824 ns | 48.6117 ns | - | 148 B |

| Exception-TryCatch | 9,253.0215 ns | 13.2496 ns | 51.3154 ns | - | 148 B |

| ExceptionMedium-Message | 14,911.7999 ns | 20.2448 ns | 78.4078 ns | - | 916 B |

| ExceptionMedium-TryCatch | 15,158.0940 ns | 147.4210 ns | 737.1049 ns | - | 916 B |

| ExceptionDeep-Message | 19,166.3524 ns | 30.0539 ns | 116.3984 ns | - | 916 B |

| ExceptionDeep-TryCatch | 19,581.6743 ns | 208.3895 ns | 833.5579 ns | - | 916 B |

| CachedException-StackTrace | 29,354.9344 ns | 34.8932 ns | 135.1407 ns | - | 1.82 kB |

| Exception-StackTrace | 30,178.7152 ns | 41.0362 ns | 158.9327 ns | - | 1.93 kB |

| ExceptionMedium-StackTrace | 100,121.7951 ns | 129.0631 ns | 499.8591 ns | 0.1953 | 15.71 kB |

| ExceptionDeep-StackTrace | 154,569.3454 ns | 205.2174 ns | 794.8034 ns | 3.6133 | 27.42 kB |

Note: in these tests we are triggering an exception every-time a method is called, they aren’t the rare cases that we measured previously.

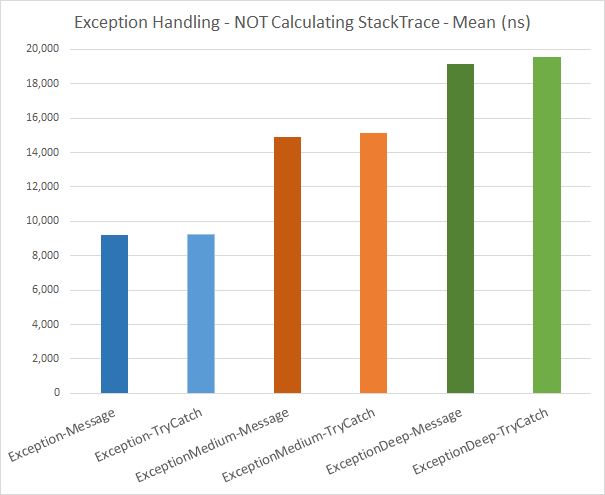

Exception handling without collecting the full StackTrace

First we are going to look at the results measuring the scenario where we don’t explicitly collect the StackTrace after the exception is caught, so the benchmark code looks like this:

[Benchmark]

public string ExceptionMessage()

{

try

{

Level20(); // start *all* the way down the stack

return null; //Prevent Error CS0161: not all code paths return a value

}

catch (InvalidOperationException ioex)

{

// Only get the simple message from the Exception

// (don't trigger a StackTrace collection)

return ioex.Message;

}

}

In the following graphs, shallow stack traces are in blue bars, medium in orange and deep stacks are shown in green

So we clearly see there is an extra cost for exception handling that increases the deeper the stack trace goes. This is because when an exception is thrown the runtime needs to search up the stack until it hits a method than can handle it. The further it has to look up the stack, the more work it has to do.

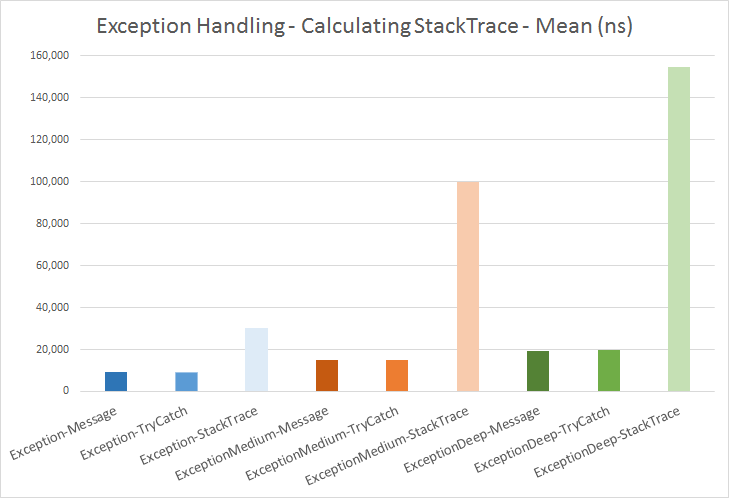

Exception handling including collection of the full StackTrace

Now for the final results, in which we explicitly ask the run-time to (lazily) fetch the full stack trace, by accessing the StackTrace property. The code looks like this:

[Benchmark]

public string ExceptionStackTrace()

{

try

{

Level20(); // start *all* the way down the stack

return null; //Prevent Error CS0161: not all code paths return a value

}

catch (InvalidOperationException ioex)

{

// Force collection of a full StackTrace

return ioex.StackTrace;

}

}

Finally we see that fetching the entire stack trace (via StackTrace) dominates the performance of just handling the exception (ie. only accessing the exception message). But again, the deeper the stack trace, the higher the cost.

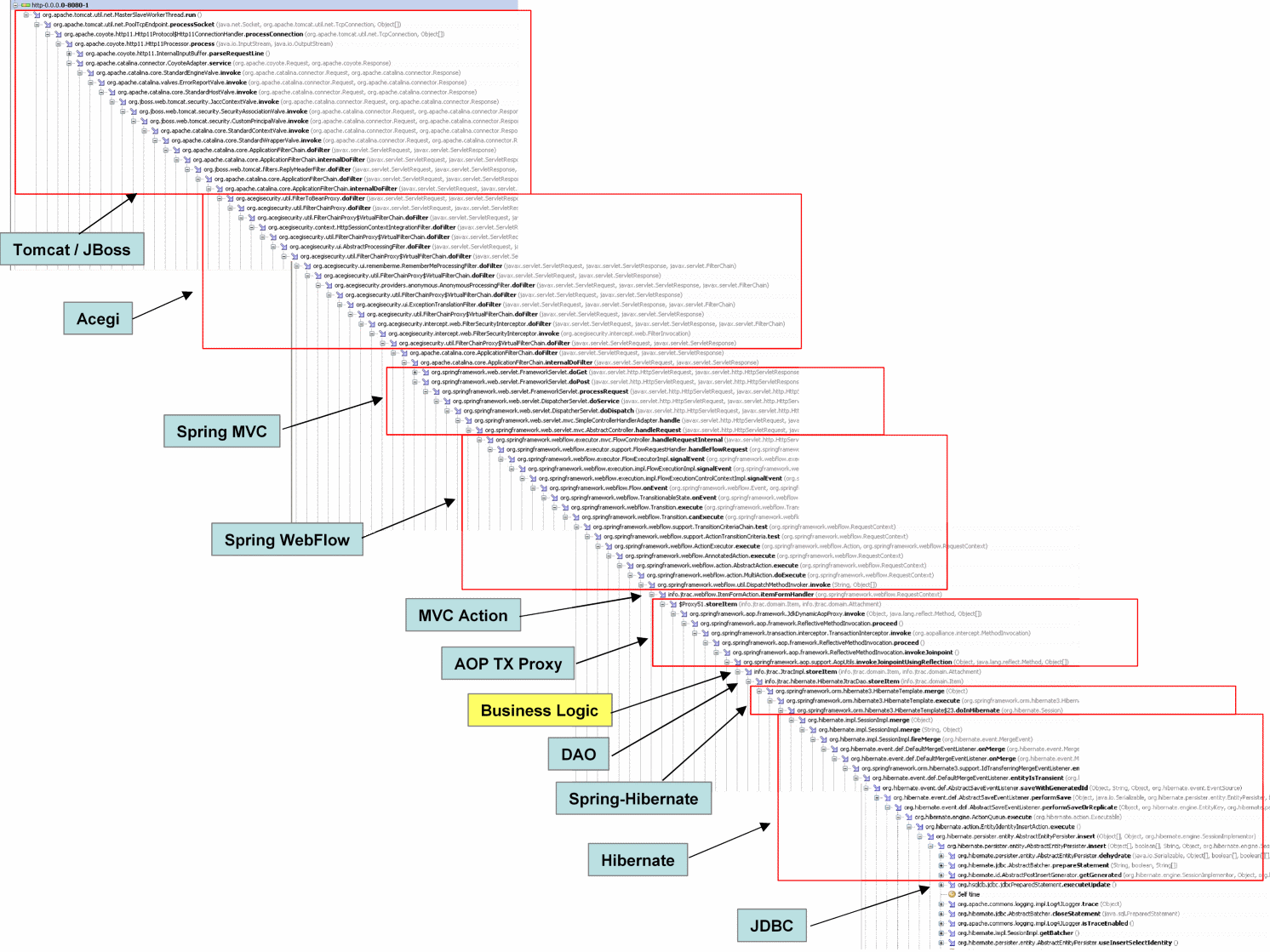

So thanks goodness we’re in the .NET world, where huge stack traces are rare. Over in Java-land they have to deal with nonesense like this (click to see the full-res version!!):

Conclusion

- Rare or Exceptional exceptions are not hugely expensive and they should always be the preferred way of error handling in .NET

- If you have code that is expected to fail often (such as parsing a string into an integer), use the

TryXXX()pattern - The deeper the stack trace, the more work that has to be done, so the more overhead there is when catching/handling exceptions

- This is even more true if you are also fetching the entire stack trace, via the

StackTraceproperty. So if you don’t need it, don’t fetch it.

Discuss this post in /r/programming and /r/csharp

Further Reading

Exception Cost: When to throw and when not to a classic post on the subject, by ‘.NET Perf Guru’ Rico Mariani.

The stack trace of a StackTrace!!

The full call-stack that the CLR goes through when fetching the data for the Exception StackTrace property

- Exception - public virtual String StackTrace

- Exception - private string GetStackTrace(..)

- Environment - internal static String GetStackTrace(..)

- Diagnostics - public StackTrace(..)

- Diagnostics - private void CaptureStackTrace(..)

- Diagnostics - internal static extern void GetStackFramesInternal(..)

- debugdebugger - DebugStackTrace::GetStackFramesInternal(..) (c/c++)

- debugdebugger - DebugStackTrace::GetStackFramesFromException(..) (c/c++)