Exploring the BBC micro:bit Software Stack

28 Nov 2017 - 2576 wordsIf you grew up in the UK and went to school during the 1980’s or 1990’s there’s a good chance that this picture brings back fond memories:

(image courtesy of Classic Acorn)

I’d imagine that for a large amount of computer programmers (currently in their 30’s) the BBC Micro was their first experience of programming. If this applies to you and you want a trip down memory lane, have a read of Remembering: The BBC Micro and The BBC Micro in my education.

Programming the classic Turtle was done in Logo, with code like this:

FORWARD 100

LEFT 90

FORWARD 100

LEFT 90

FORWARD 100

LEFT 90

FORWARD 100

LEFT 90

Of course, once you knew what you were doing, you would re-write it like so:

REPEAT 4 [FORWARD 100 LEFT 90]

BBC micro:bit

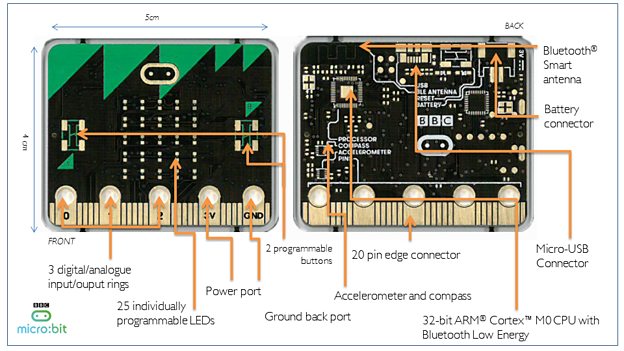

The original Micro was launched as an education tool, as part of the BBC’s Computer Literacy Project and by most accounts was a big success. As a follow-up, in March 2016 the micro:bit was launched as part of the BBC’s ‘Make it Digital’ initiative and 1 million devices were given out to schools and libraries in the UK to ‘help develop a new generation of digital pioneers’ (i.e. get them into programming!)

Aside: I love the difference in branding across 30 years, ‘BBC Micro’ became ‘BBC micro:bit’ (you must include the colon) and ‘Computer Literacy Project’ changed to the ‘Make it Digital Initiative’.

A few weeks ago I walked into my local library, picked up a nice starter kit and then spent a fun few hours watching my son play around with it (I’m worried about how quickly he picked up the basics of programming, I think I might be out of a job in a few years time!!)

However once he’d gone to bed it was all mine! The result of my ‘playing around’ is this post, in it I will be exploring the software stack that makes up the micro:bit, what’s in it, what it does and how it all fits together.

If you want to learn about how to program the micro:bit, its hardware or anything else, take a look at this excellent list of resources.

Slightly off-topic, but if you enjoy reading source code you might like these other posts:

- The 68 things the CLR does before executing a single line of your code

- A Hitchhikers Guide to the CoreCLR Source Code

- DotNetAnywhere: An Alternative .NET Runtime

BBC micro:bit Software Stack

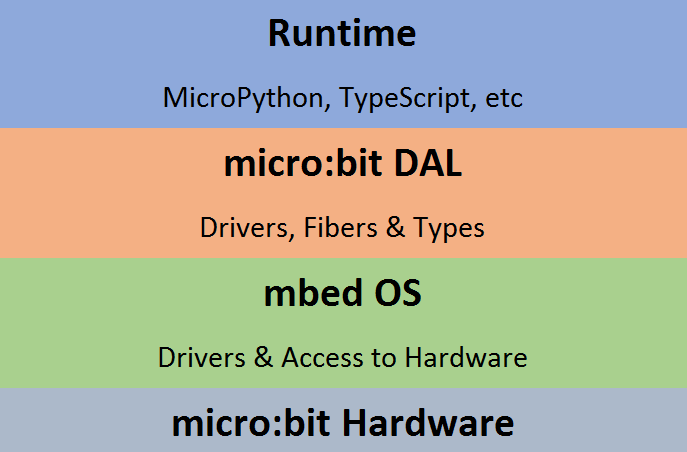

If we take a high-level view at the stack, it divides up into 3 discrete software components that all sit on top of the hardware itself:

If you would like to build this stack for yourself take a look at the Building with Yotta guide. I also found this post describing The First Video Game on the BBC micro:bit [probably] very helpful.

Runtimes

There are several high-level runtimes available, these are useful because they let you write code in a language other than C/C++ or even create programs by dragging blocks around on a screen. The main ones that I’ve come across are below (see ‘Programming’ for a full list):

- Python via MicroPython

- JavaScript with Microsoft Programming Experience Toolkit (PXT)

- well actually it’s TypeScript, which is good, we wouldn’t want to rot the brains of impressionable young children with the horrors of Javascript - Wat!!

They both work in a similar way, the users code (Python or TypeScript) is bundled up along with the C/C++ code of the runtime itself and then the entire binary (hex) file is deployed to the micro:bit. When the device starts up, the runtime then looks for the users code at a known location in memory and starts interpreting it.

Update It turns out that I was wrong about the Microsoft PXT, it actually compiles your TypeScript program to native code, very cool! Interestingly, they did it that way because:

Compared to a typical dynamic JavaScript engine, PXT compiles code statically, giving rise to significant time and space performance improvements:

- user programs are compiled directly to machine code, and are never in any byte-code form that needs to be interpreted; this results in much faster execution than a typical JS interpreter

- there is no RAM overhead for user-code - all code sits in flash; in a dynamic VM there are usually some data-structures representing code

- due to lack of boxing for small integers and static class layout the memory consumption for objects is around half the one you get in a dynamic VM (not counting the user-code structures mentioned above)

- while there is some runtime support code in PXT, it’s typically around 100KB smaller than a dynamic VM, bringing down flash consumption and leaving more space for user code

The execution time, RAM and flash consumption of PXT code is as a rule of thumb 2x of compiled C code, making it competitive to write drivers and other user-space libraries.

Memory Layout

Just before we go onto the other parts of the software stack I want to take a deeper look at the memory layout. This is important because memory is so constrained on the micro:bit, there is only 16KB of RAM. To put that into perspective, we’ll use the calculation from this StackOverflow question How many bytes of memory is a tweet?

Twitter uses UTF-8 encoded messages. UTF-8 code points can be up to six four octets long, making the maximum message size 140 x 4 = 560 8-bit bytes.

If we re-calculate for the newer, longer tweets 280 x 4 = 1,120 bytes. So we could only fit 10 tweets into the available RAM on the micro:bit (it turns out that only ~11K out of the total 16K is available for general use). Which is why it’s worth using a custom version of atoi() to save 350 bytes of RAM!

The memory layout is specified by the linker at compile-time using NRF51822.ld, there is a sample output available if you want to take a look. Because it’s done at compile-time you run into build errors such as “region RAM overflowed with stack” if you configure it incorrectly.

The table below shows the memory layout from the ‘no SD’ version of a ‘Hello World’ app, i.e. with the maximum amount of RAM available as the Bluetooth (BLE) Soft-Device (SD) support has been removed. By comparison with BLE enabled, you instantly have 8K less RAM available, so things start to get tight!

| Name | Start Address | End Address | Size | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| .data | 0x20000000 | 0x20000098 | 152 bytes | 0.93% |

| .bss | 0x20000098 | 0x20000338 | 672 bytes | 4.10% |

| Heap (mbed) | 0x20000338 | 0x20000b38 | 2,048 bytes | 12.50% |

| Empty | 0x20000b38 | 0x20003800 | 11,464 bytes | 69.97% |

| Stack | 0x20003800 | 0x20004000 | 2,048 bytes | 12.50% |

For more info on the column names see the Wikipedia pages for .data and .bss as well as text, data and bss: Code and Data Size Explained

As a comparison there is a nice image of the micro:bit RAM Layout in this article. It shows what things look like when running MicroPython and you can clearly see the main Python heap in the centre taking up all the remaining space.

microbit-dal

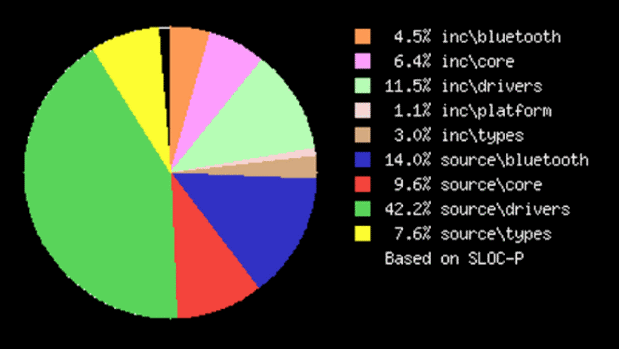

Sitting in the stack below the high-level runtime is the device abstraction layer (DAL), created at Lancaster University in the UK, it’s made up of 4 main components:

- core

- High-level components, such as

Device,Font,HeapAllocator,ListenerandFiber, often implemented on-top of 1 or moredriverclasses

- High-level components, such as

- types

- Helper types such as

ManagedString,Image,EventandPacketBuffer

- Helper types such as

- drivers

- For control of a specific hardware component, such as

Accelerometer,Button,Compass,Display,Flash,IO,SerialandPin

- For control of a specific hardware component, such as

- bluetooth

- All the code for the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) stack that is shipped with the micro:bit

- asm

- Just 4 functions are implemented in assembly, they are

swap_context,save_context,save_register_contextandrestore_register_context. As the names suggest, they handle the ‘context switching’ necessary to make the MicroBit Fiber scheduler work

- Just 4 functions are implemented in assembly, they are

The image below shows the distribution of ‘Lines of Code’ (LOC), as you can see the majority of the code is in the drivers and bluetooth components.

In addition to providing nice helper classes for working with the underlying devices, the DAL provides the Fiber abstraction to allows asynchronous functions to work. This is useful because you can asynchronously display text on the LED display and your code won’t block whilst it’s scrolling across the screen. In addition the Fiber class is used to handle the interrupts that signal when the buttons on the micro:bit are pushed. This comment from the code clearly lays out what the Fiber scheduler does:

This lightweight, non-preemptive scheduler provides a simple threading mechanism for two main purposes:

1) To provide a clean abstraction for application languages to use when building async behaviour (callbacks). 2) To provide ISR decoupling for EventModel events generated in an ISR context.

Finally the high-level classes MicroBit.cpp and MicroBit.h are housed in the microbit repository. These classes define the API of the MicroBit runtime and setup the default configuration, as shown in the Constructor of MicroBit.cpp:

/**

* Constructor.

*

* Create a representation of a MicroBit device, which includes member variables

* that represent various device drivers used to control aspects of the micro:bit.

*/

MicroBit::MicroBit() :

serial(USBTX, USBRX),

resetButton(MICROBIT_PIN_BUTTON_RESET),

storage(),

i2c(I2C_SDA0, I2C_SCL0),

messageBus(),

display(),

buttonA(MICROBIT_PIN_BUTTON_A, MICROBIT_ID_BUTTON_A),

buttonB(MICROBIT_PIN_BUTTON_B, MICROBIT_ID_BUTTON_B),

buttonAB(MICROBIT_ID_BUTTON_A,MICROBIT_ID_BUTTON_B, MICROBIT_ID_BUTTON_AB),

accelerometer(i2c),

compass(i2c, accelerometer, storage),

compassCalibrator(compass, accelerometer, display),

thermometer(storage),

io(MICROBIT_ID_IO_P0,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P1,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P2,

MICROBIT_ID_IO_P3,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P4,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P5,

MICROBIT_ID_IO_P6,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P7,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P8,

MICROBIT_ID_IO_P9,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P10,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P11,

MICROBIT_ID_IO_P12,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P13,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P14,

MICROBIT_ID_IO_P15,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P16,MICROBIT_ID_IO_P19,

MICROBIT_ID_IO_P20),

bleManager(storage),

radio(),

ble(NULL)

{

...

}

mbed-classic

The software at the bottom of the stack is making use of the ARM mbed OS which is:

.. an open-source embedded operating system designed for the “things” in the Internet of Things (IoT). mbed OS includes the features you need to develop a connected product using an ARM Cortex-M microcontroller.

mbed OS provides a platform that includes:

- Security foundations.

- Cloud management services.

- Drivers for sensors, I/O devices and connectivity.

mbed OS is modular, configurable software that you can customize it to your device and to reduce memory requirements by excluding unused software.

We can see this from the layout of it’s source, it’s based around common components, which can be combined with a hal (Hardware Abstraction Layers) and a target specific to the hardware you are running on.

More specifically the micro:bit uses the yotta target bbc-microbit-classic-gcc, but it can also use others targets as needed.

For reference, here are the files from the common section of mbed that are used by the micro:bit-dal:

- board.c

- error.c

- FileBase.cpp

- FilePath.cpp

- FileSystemLike.cpp

- gpio.c

- I2C.cpp

- InterruptIn.cpp

- pinmap_common.c

- RawSerial.cpp

- SerialBase.cpp

- Ticker.cpp

- ticker_api.c

- Timeout.cpp

- Timer.cpp

- TimerEvent.cpp

- us_ticker_api.c

- wait_api.c

And here are the hardware specific files, targeting the NORDIC - MCU NRF51822:

- analogin_api.c

- gpio_api.c

- gpio_irq_api.c

- i2c_api.c

- pinmap.c

- port_api.c

- pwmout_api.c

- retarget.cpp

- serial_api.c

- startup_NRF51822.S

- system_nrf51.c

- twi_master.c

- us_ticker.c

End-to-end (or top-to-bottom)

Finally, lets look a few examples of how the different components within the stack are used in specific scenarios

Writing to the Display

- microbit-dal

- MicroBitDisplay.cpp, handles scrolling, asynchronous updates and other high-level tasks, before handing off to:

- mbed-classic

void port_write(port_t *obj, int value)in port_api.c (‘NORDIC NRF51822’ version), via a call tovoid write(int value)in PortOut.h, using info from PinNames.h

Storing files on the Flash memory

- microbit-dal

- Provides the high-level abstractions, such as:

- FileSystem

- File

- Flash

- mbed-classic

- Allows low-level control of the hardware, such as writing to the flash itself either directly or via the SoftDevice (SD) layer

In addition, this comment from MicroBitStorage.h gives a nice overview of how the file system is implemented on-top of the raw flash storage:

* The first 8 bytes are reserved for the KeyValueStore struct which gives core

* information such as the number of KeyValuePairs in the store, and whether the

* store has been initialised.

*

* After the KeyValueStore struct, KeyValuePairs are arranged contiguously until

* the end of the block used as persistent storage.

*

* |-------8-------|--------48-------|-----|---------48--------|

* | KeyValueStore | KeyValuePair[0] | ... | KeyValuePair[N-1] |

* |---------------|-----------------|-----|-------------------|

Summary

All-in-all the micro:bit is a very nice piece of kit and hopefully will achieve its goal ‘to help develop a new generation of digital pioneers’. However, it also has a really nice software stack, one that is easy to understand and find your way around.

Further Reading

I’ve got nothing to add that isn’t already included in this excellent, comprehensive list of resources, thanks Carlos for putting it together!!

Discuss this post on Hacker News or /r/microbit